Tea and Topics of Transgression. On Architecture and Gender

Anna Ingebrigtsen

In this essay I provide a view into the middle of a conversation held between a friend and me. It is a framed insight to a discussion of three main topics: feminist architectures, architectural practice and the woman architect. The structure of the essay moves between a dialogue and my own musings on the topics we discuss. The conversation itself is based on a true event, but has been adapted to meet my goals for this paper. After examining numerous readings, projects and practices on the topics of gender, space and architecture, I felt the need to take this opportunity to reflect on them, and to question my position in my own education, beliefs and method of design. These are questions I have met and danced with but not yet sat down and had a conversation with. I noticed that while speaking with my friend, I used analogies and specific personal examples to explain questions or theories I found difficult to articulate. I later marveled at why I did this and why I thought it was effective. I realize that though my experiences are unique, they may not be uncommon among other female architects. Here I use writing as a tool and mode ofexploration in determining my position.

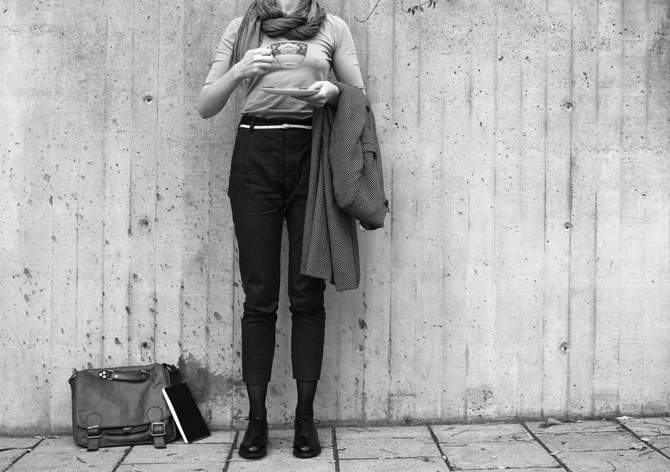

I was having tea with my friend Alex last week and he asked me what I was working on in school. When Alex asked me to describe what feminist architecture looks like, I was overcome with explanations and I had trouble giving him a clear answer. How, if at all, can feminist architecture be identified or visually distinguished from other architectures? He mentioned observing some intimidating phallic skyscrapers (erected masculine ego and patriarchal symbol) of North America and Great Britain.

He then asked, “So does Feminist Architecture appear more curvilinear, undulating and welcoming?“ “I suppose it could,” I said. “But there is more to it than that.”

I think Feminist Architecture can no sooner be an architectural style than Feminism itself can be a unified solidarity. Some say architecture reflects the philosophy and ideals of a society, but realizing a consolidated visual form for the many interpretations of feminism would be issuing, in a way, a dogmatic operation.

The truth is that I had also been asking myself these questions. Are there characteristic physical features of feminist design? I rather think not. But perhaps the question I needed to ask was: how can feminist approaches operate in design? Alex was looking for a tangible answer, or a clear-cut definition. At the time, I cursed inwardly at not being able to articulate a clear response. However, over the next two cups of tea, I experienced a transgression. I had swung onto a new train of thought, stumbling, pushing forward, in rambling fits and starts. This is where I would move through my questions, open doors to new places, and continue on a dynamic trajectory locating myself in the futures of architecture. The conversation with my friend became a place of experiment, and a venture into the ‘neither-space’ that is neither this nor that, but the journey through the wilderness in between or what Helene Frichot–with reference to Deleuze and Guattari–describes as a “line of flight” (Frichot 2010, 318).

“So then, you use feminist methodologies in the process?”, Alex asked.

“Yes. To me that means always questioning/challenging the norm and through maintaining a critical position, finding positive alternatives. We may alter, undermine or subvert current conditions to include our own voices. We can do this by experimenting with methods of research, design methodologies, epistemologies and employing specific strategies, tactics, and tools.”

“But why is that different from a typical architectural practice?” he asked.

“In my previous school and work experiences, there has been a general lack of discourse on social issues. It hasn’t been emphasized or highly valued. In this arena, it is the first consideration.”

I began telling him of my current design project: There is an extreme housing shortage and consequent social and spatial segregation in Stockholm. Our studio seek to react against homogenous trends, work towards social diversity and encourage a debate about the city through our work. We are inventing new sets of rules, engaging self- organizing frameworks for activating equal participation, appropriation tactics, and subversive strategies. Our focus is Do-it-Yourself design, political imagination, acknowledging ‘in-between’ spaces and drawing attention to the limitless opportunities for cultivation of collective space, or as Pratibha Parma has formulated it: “The appropriation and use of space are political acts” (quoted in Hooks 2000, 209).

“So how does this critical theory and this specialization in school translate into professional practice?” Alex ventured.

This brought me to the subject of Architectural Practice. The current architectural firm in general is OK. In my experience, there appears to be equal opportunity and chances at advancement in many countries. A former female colleague stated, “I’ve never felt any type of discrimination while working in architecture... I feel that the people who do advance are those who become registered and who prove that they are able to successfully run projects independently and hold their own at meetings, despite their gender.” I feel conflicted here because I recognize how the inherent patriarchal value systems and hierarchical frameworks of architectural firms in history have left residue in those found today. This is problematic because that residue can be sexist, oppressive and highly gender-discriminate. But to express this I had to first tell Alex about my time in Vancouver...

After my undergraduate degree I left The Canadian Prairies and headed west. I applied and was hired at my first choice firm in Vancouver. It is one of the most reputable landscape architecture and sustainable urbanism firms in Western Canada and has a project list worthy of praise. One aspect initially attracting me to this firm is that one of the partners is female. She is a head-strong, successful and admirable business woman; I looked forward to learning from such a role model. But I would later find that she was more macho than many men in the field and had adopted a dominating masculine attitude as a way to survive competition.

When I arrived at my new job there were 29 employees: 14 male, 12 female plus 3 female administration staff. From the outside this is a fairly even mix; but, let’s look a little closer. The positions of power are held mostly by men, with 3 male partners to one female, and 3 male associates also to one female. Men generally held the project leader titles and women usually held supporting roles or were occasionally given smaller projects of their own, overseen by a project manager. I wondered what mechanism existed that allowed the men to juggle a successful career and a family while women were rarely seen to do either. 57% of men in the office had wives at home or with flexible jobs, raising children and caring for the household. No women had a full-time stay-at-home partner. 60% of the women were single while no men were single. These figures suggest that the roles of power in the firm were correlated to their ability to fully devote their time to work. A former female colleague of mine claims to have been laid off from her firm after inquiring into the maternity leave policy, “because I could potentially become pregnant.” Another former colleague recalls a previous firm partner stating “I prefer to hire men because they won’t leave to have children.” As Doreen Massey states,

The point is that the whole design of these jobs requires that such employees do not do the work of reproduction and caring for other people; indeed it implies that, best of all, they have someone to look after them (Massey 2000, 132).

“Sounds like an unbalanced sexual division of labour,” commented Alex. “Is there something more being offered to men which limits women gaining higher positions?”

“It seems that much of the knowledge valued in this firm came from first-hand experience in the field. For example, many of the men spent summers over the years in construction or landscaping. These jobs are typically not available for women. I found such previous work experiences were directly linked to the positions within the firm.”

I remember working as a designer at a small landscaping business in my hometown. I spent two summers there, watching women rejected from the advertised landscaping jobs. These women were equally as strong as any male applicants and had at least an equal level of education. Though acknowledged as competent for the job, they were discriminated against because they were seen as distractions and targets of harassment for the men at work, an appalling policy. As Sandra Harding states on the subject, “It is not fair to exclude women from gaining the benefits of participating in these enterprises that men get” (Harding 1987, 7). I spoke with the principal about this and we agreed that I would henceforth split my time between the crew and the office. I explained that it would increase my knowledge of construction and strengthen my expertise in the business. Working with the crew was fun and educational. The men were not sexist but helpful and fun to work with. I believe design-builds are an important part of our education and that it is an injustice that few women have the opportunity to learn through construction.

None of the women at the Vancouver firm had this opportunity, which in turn, contributed to the creation of a glass ceiling for advancement in many of their careers. A reoccurring, confidence-crushing operation was to be given a design assignment from a partner, execute it efficiently, and then see our work pushed aside and redone by a male partner/ associate. This action diminished our work and added to the view that men continuously drew ahead while we failed to achieve. Many of the women I knew at this firm suffered feelings of doubt, inadequacy, confusion and rage. Six women (and no men) have quit in the last year to seek work elsewhere or start their own practices. A former female colleague asks, “Why have I never been promoted to a higher position since my employers value my work ethic, experience, and knowledge?”

“It’s infuriating to realize that you have to work twice as hard as any male on the job, and still may not gain the same opportunities, recognition and achievements,” I said.

Alex responded “But surely you could have raised these issues with one or more of the partners and resolved to make some improvements?”

“Yes of course, and we often did. Seeing results are something else entirely, these problems are deeply ingrained. For instance, one day I was discussing the matter of site visits with some female designers over lunch. I was expressing my desire to visit some of the sites I was designing for. A senior director entered and shortly after declared that I was wrong in “feeling entitled to knowledge which takes years to accumulate the right for.” In 2 years I went on 3 official site visits. A male colleague and friend of the same age had been given a large project and went on weekly site visits. I took one afternoon off in “over-time hours” and joined him. I saw the construction process and how a field review is performed, although such mentorship would ideally be done with a good partner. I met many of the men working there, and they happily explained their roles and the overall progress of the construction.

The sexist practices (whether conscious or unconscious) built into firm life and the construction industry must be undone to achieve equality for women architects. Jane Rendell explains that the women on the outside of these structures are “in an excellent position to create alternative horizontal networks, where relations and dynamics of power could be constructed differently” (Rendell 2007, 72). Lynne Walker reinforces noting “the primary importance of changing the existing design process so that women are involved in decision-making at every stage” (Walker 2000, 244). My working experiences have greatly transformed my conceptions of practice. I have been naive in the amount of unfinished business feminists have yet to work through.

This knowledge has caused my academic work to mature as my critical thinking skills have strengthened and my imagination activated. Gender and power are complex issues and by examining them I hope to conceptualize and engage in new visions of power relations, economies, value systems, and design methodologies within and beyond architecture.

Alex and I began discussing how women have had to fight for inclusion in a predominantly male profession, from acceptances in academic institutions to establishing themselves as professional architects.

“...And though in most universities, the male-female student ratio is equal, men still make up the majority of architects in the profession,” I said.

“How do you hope to impact and improve the practice of architecture?”

I began thinking of the changes I would make, but to better explain this, I had to tell him about rock climbing...

Rock climbing has a male-heavy past, but today climbers could argue that it is a primarily gender-blind sport. Sports tend to reward strength, speed and height, traits where men hold a physical advantage. But in the three years since I started climbing, I’ve consistently witnessed women match or best the efforts of much burlier men. Many probably assume that men, as in many other sports, are stronger, faster and go higher. But men regularly depend on their brute strength when beginning to climb. They are seen forcing their way up a wall and quickly exhaust themselves. Whereas women, not accustomed to taking muscle mass for granted, instantly exhibit strategic maneuvers in their movements. We distribute our strength and use momentum over power. You see, climbers cannot rely on brute strength alone. When it comes to balance, body position and flexibility, women often have the advantage. Though many top climbers are men, in some cases, women have accomplished what men could not. It is rare to see mixed-sex teammates in sports and competitions, but with climbing, it is as common as chalk. Here exist potential for understanding and enhancing each others strengths and creating more equal teams and practices.

In this way, women have entered a traditionally male sphere, the sport of climbing, and succeeded in strengthening, altering and improving it. While climbing is not the only example of this, through our conversation, Alex found a lens through which to view achieving change in the architectural world, and I began developing techniques for thinking and speaking about it. By trusting and pushing our existing expertise and appropriating traditional methods, women can continue to (re)build these environments. Our generation of architects has immense potential and responsibility for innovation in practice– in the office, the field and the mind. Sometimes it only takes a conversation over a cup of tea to begin.¤

References

Frichot, Hélène. 2010. “Following Hélène Cixous’ Steps Towards A Writing Architecture.” Architectural Theory Review 15:3; 312 – 323.

Harding, Sandra. 1987. “Is There a Feminist Method?” In Feminism and Methodology: Social Science Issues, edited by Sandra Harding, 1-13. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Massey, Doreen. 2000. “Space, Place and Gender.” In Gender Space Architecture, edited by Jane Rendell et al. 128-133. London: Routledge.

Parma, Pratibha as quoted by bell hooks. 2000. “Choosing the Margin as a Place of Radical Openness.” In Gender Space Architecture, edited by Jane Rendell et al. 203-209. London: Routledge.

Rendell, Jane. 2007. “How to Take Place (but only for so long)” In Altering Practices, edited by Doina Petrescu. 69-88. Oxon: Routledge.

Walker, Lynne. 2000. “Woman and Architecture” In Gender Space Architecture, edited by Jane Rendell et al. 244-257. London: Routledge.

Bio

Anna Ingebrigtsen is a fifth-year architecture thesis student in Critical Studies Design Studio at KTH. She has studied in Canada, The Netherlands and Sweden. Anna is interested in relationships between architecture and critical feminist theory and methodologies, alternative cultural productions, and sustainable landscapes. How can we explore new ways to conceptualize and articulate more expansive visions of the future? Her favourite tea is chai with milk and honey.